The first draft of The Vanishing Room is complete; that’s more than thirty chapters of delicately spun fiction that needs to survive the critical deductions of countless smart readers. Thinking about this drowns me in an ocean of paranoia. What if something doesn’t fit? What if there is a latent ice-box moment waiting to spoil the readers’ enjoyment?

To counteract the effects of this anxiety, I am making use of a number of tricks and techniques that I hope to uncover inconsistencies and weaknesses before anyone else reads the manuscript. I thought I’d share some of the tricks for anyone who is interested.

Research

You just can’t research too much. I’m sketching my plot around real places and setting the story in a real year. For the places, I need to view lots of photographs and read broadly enough to be able to represent the locations fairly and accurately. This also means getting out into the real world to see these places for myself, because you need to submerge more than just your eyes if you want to write about a place. By breathing in the air, drowning in the sounds, and feeling the dirt between your toes you can describe how the place makes you feel. Without engaging these other senses, the places become thin and lifeless.

I’m a fan of using real dates. Not just a year, but the months and days in that year. The Vanishing Room begins on 26th October 2015. That was a Monday. It was generally cool in France in this week – between 16°C and 22°C and with only a brief splash of rain. There was a full-moon on the 27th October, although it would have looked full for a few days. Although 2015 is only a few years ago, I checked that the modes of transport existed, and what stations and airports would have been called at that time. There had been terrible floods on the French Riviera early that month, a number of shocking terrorist attacks, and a plane crash in the alps that was attributed to the suicide of the co-pilot. Serena Williams won the French Open at Roland Garos. Chris Froome won the Tour de France.

This is just a flavour of what you’ll find when you start to fill in the background of times and places. You’ll read a great deal, but use just a little. I suppose you could say that you are after the zest of the year rather than the whole lemon.

Tangled Web

Given that you created the people and plot in your story, you’d think you’d need to research them less. I find that the complex web of fiction needs more research and cross-checking than real life. When it comes to real life, it is naturally credible (even when it seems incredible). Fiction needs a lot of care and attention to maintain credibility. Mistakes can range from a simple continuity errors, to plot disconnects that break the entire illusion.

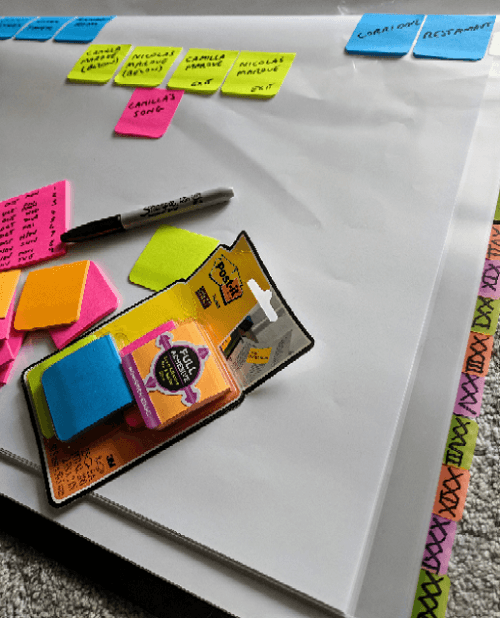

To help expose these problems, I create a visual representation of each chapter on an A3 sheet. I use small sticky-notes to connect characters and events to their times and places. This highlights many kinds of issue, for example where people leave the room but then speak, or when a return journey doesn’t match the outward leg. By re-scanning this visual map, you can also detect bigger problems in your story that aren’t obvious at street-level when you are working on the text itself.

Flash Cards

I need constant reminders of some things, such as how a character senses and responds to a place, person, or event. I proof-read with flash cards to remind me to test out a chapter against these easy-to-neglect writing elements.

Rest Those Tired Eyes

The final trick I use is to use text-to-speech, or a willing friend, to read the book out loud. Listening to the story instead of reading it suddenly exposes issues with the plot, and with the words themselves. By switching the input method, you notice different parts of the work.

This is worth repeating several times – and after major revisions.

Summary

This is just a selection of ideas that help me with my writing – and with my mental state while writing. You may find some of them are useful to you too.